Both Thomas Bewick and his son Robert had strong links with Tynemouth, and also a social and commercial relation with early members of the Spence / Foster family. In the later 19thC several members of this family were involved in piping.

THOMAS BEWICK visited Tynemouth frequently, and it was there that he wrote the first part of his Memoir during November and December 1822. One of his many friends was Robert Foster of Tynemouth, the father-in-law of Robert Spence (and therefore a progenitor of the Spence / Watson family). Foster knew Bewick well enough to call on him unexpectedly at home, as reported by the geologist Adam Sedgewick who was taken by Foster to meet Bewick whilst they were out walking. In view of this it seems likely that Bewick would have visited Foster when staying in Tynemouth.

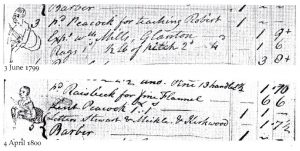

Thomas Bewick was a piping enthusiast and although there is no evidence that played pipes, he ensured that his son Robert was tutored by a recognised master of traditional piping, John Peacock. Thomas’s account books show entries of payments for Robert’s tuition and other piping costs, starting in 1788, and against some of these he drew a total of five marginal sketches of his son, all of which are consistent in general appearance:

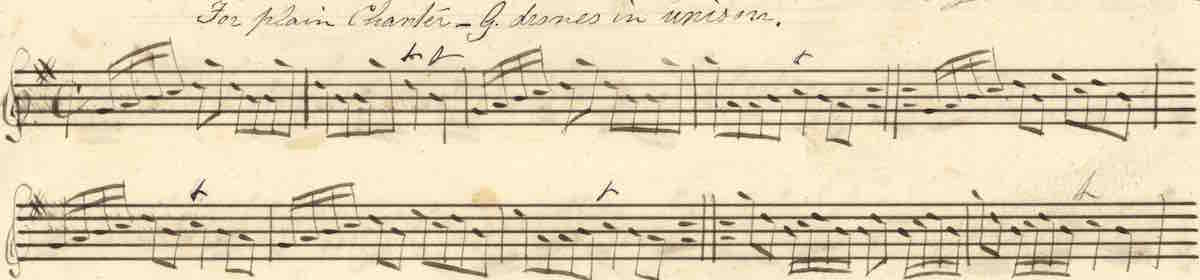

In addition to tuition fees, the expenses covered unspecified cash payments, a music book, repairs to bellows, and music ‘pricked out’ by a Mr. Aldridge and a Mr. Halgarth (possibly William Halgarth, printer and bookseller of South Shields). In July of 1800 Bewick paid 14/- (14 shillings, or 70 new pence) for a new chanter. In his important essay about piping expenses recorded in Thomas Bewick’s accounts, Iain Bain suggests that this might have been the newly-developed keyed chanter. In 1801 Bewick was at charges for the repair of Robert’s chanter, and in 1802 for a new bag. A reference in 1809 to payment for a “lesson on the New Pipes” might suggest that Robert was given a new, multi-keyed set of pipes for his coming of age.

In his Memoir Thomas relates that he asked “old William Lamshaw, the Duke of Northumberland’s Piper” to play at a theatre for the impresario Charles Dibdin (NB Bewick spelled the as Dibden name in his Memoir) after Dibdin’s entire company were in dispute over earnings and had refused to perform. This probably took place around the early- to mid- 1770s, and implies that Thomas knew Lamshaw (the grandfather of the younger William) reasonably well, and so may well also have know the younger William, especially when both were in North Shields / Tynemouth between c.1798 and 1806.

As a youngster ROBERT BEWICK was an enthusiastic, and perhaps even mildly obsessive piper. The repairs to his chanter and the replacement of his pipe bag suggest heavy usage. In 1801 Thomas wrote from Tynemouth to his sister-in-law, “Little Rob: is (while I am writing this) playing John’s new tunes of peace & plenty &c to old Willie Dean, in the Kitchen …“, and in 1799 Robert himself writes to his sister, “… and when I was in the country I played all my Tunes at Eltringham and Mount Hooly, and I would have been glad to go to Shields to play all my Tunes at Betty Skipsey’s Birth Day but my father dare not trust me out of his sight ….“. Neither Willie Dean nor Betty Skipsey have yet been identifed with certainty and, unfortunately, Robert’s term “Shields” is ambiguous and could refer to either North or South Shields.

The British Museum holds a drawing by Robert Bewick, illustrating his view Tynemouth castle and the pharos lighthouse from the north. It is not possible to precisely date the drawing from internal evidence:

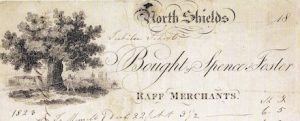

Both Thomas and, later, Robert Bewick had commercial links with the Foster and Spence familes. Examples include bookplates that Thomas produced for Robert Spence in 1808, and a billhead etched by Robert for Spence & Foster, Raff Merchants in 1819:

There is also, in the archives of the Northumberland Natural History Society, a pen & ink study by Robert for a billhead showing the shop owned by Spence & Proctor which stood on the corner of Howard Street and Tyne Street in North Shields:

Although it must remain speculation, it seems probable that Thomas would have visited his friend Robert Foster while in Tynemouth, and would have known his family. It is possible, even likely, that Robert would also have met them. If this was so, then it is tempting to imagine that the young, mildly obsessive, piper might have been allowed the opportunity to “to play all my Tunes” to his father’s friends, and so might even have stimulated that family’s awareness of Northumberland piping.

As an adult Robert sustained his early interest in piping. He kept and maintained the manuscript tunebooks which may, perhaps, have been started by John Peacock. More than two decades after Robert’s death his sisters gave the tunebooks to Joseph Crawhall.

There are contemporary accounts of Robert’s playing as an adult. In April 1827 the great American ornithologist John James Audubon visited Thomas Bewick at his home. He met the “amiable and affable” Misses Bewick, and talked at length with the 74-year-old Thomas, and afterwards:

“The tea-drinking having in due time come to an end, young Bewick, to amuse me, brought a bagpipe of a new construction, called the Durham Pipe, and played some simple Scotch, English and Irish airs, all sweet and pleasing to my taste. I could scarcely understand how, with his large fingers he managed to cover each hole separately. The instrument sounded somewhat like a hautboy, and had none of the shrill warlike notes or booming sound of the military bagpipe of the Scotch Highlanders. The company dispersed at any early hour, and when I parted from Bewick that night I parted from a friend.”

In his 1842 work “Visits to Remarkable Places” William Howitt writes of hearing pipes during an earlier journey through Northumberland:

“The Northumbrian pipe is a most lively and inspiriting instrument ; and when the old marches and border tunes, which so long animated the Northumbrian race in the contests with the Scots, or at their times of festivity, are played upon it, we cannot help wondering that it has become so much neglected. During my last ramble through this country I only chanced to hear it thrice—once at Keildar Castle [sic], once at Bamborough [sic] , and thirdly, and best, by Mr. Robert Bewick, at Gateshead. Mr. Bewick, the celebrated engraver, with that love for whatever was characteristic of his native county, had his son taught to play on this pipe, that he might do as much as he could to keep up its use ; and those who have heard his son play it, as I have done, will sincerely wish that its use was more general.”

Perhaps the best known is the account given by the artist Willam Scott Bell in his auobiography of 1860:

“Robert was one of the last remaining adepts on the small Northumberland bagpipes, and we were shortly after invited to take tea at a friend’s house for the purpose of hearing him. He appeared, carrying the union-pipes under his arm, accompanied by two tall old-fashioned maiden sisters; but when the time arrived for his performance, he seemed as scared as some men are who have to make a public speech, and was evidently inclined to run away. Our host, however, who knew him well, proposed that he should tune his instrument on the landing outside the drawing-room door, which was a formula he appeared to understand; and after the tuning he played there, and we heard him perfectly, and applauded him much. The ice thus broken, he soon gained confidence, re-entered the room, and walked about excitedly playing Scotch airs with variations in the loveliest manner on that most delicate of native instruments.”

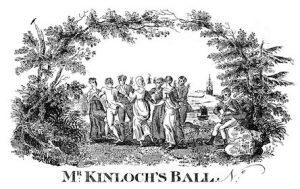

The Bewicks are linked with John Peacock. John Peacock is linked through the Newcastle Volunteers’ Concerts and other events to identifiable local musicians including Alexander Kinloch (also spelt Kinlock). The Bewicks, though, also have a proven link with Alexander Kinloch; in c.1812 Robert engraved the copperplate from Thomas’s preliminary pencil study for tickets for “Mr. Kinloch’s Ball”. This portrays four women and three men dancing in a circle to a Northumberland piper’s music. The scene is set in a sylvan grove with a view to the distinctive crown on the spire of St Nicholas’ parish church (now the Anglican cathedral), across the river on which is seen a square-sailed Tyne keel under sail. Given that Robert engraved this it might be assumed that the portrayal of the piper is accurate, and possibly even a representation of himself.

One interesting feature of this image, and also of the marginalia in Thomas Bewick’s account books, is that the drones of the pipes are held at quite a steep angle, rather higher than the more horizontal position typical of today’s players. This may reflect an early playing style.

Two of the tunes in Robert Bewick’s Mss note-books have titles relevant to North Shields and Tynemouth; one of these is “New Road to Tynemouth” and the other is “Shields Fair”.