James Fenwick’s manuscript contains significant evidence about the music played by the Reid family. It includes 14 tunes (including two different versions of ‘Jacky Layton’) specifically attributed to Robert (III), James, and/or Elizabeth Reid. Thirteen of these are transcriptions but one is hand-written on a separate sheet of paper pasted into the book, and may have been written out by Elizabeth Reid.

On this page of the website, after the section on specific tunes named in Fenwick, there is a section about tunes which may have been played by the Reids, but for which there is no specific evidence.

REID TUNES FROM THE FENWICK MANUSCRIPT

The tunes in Fenwick are described below in the order in which they appear in the manuscript. The brief n0tes that accompany them will be expanded as research and time allows. Fenwick’s transcripts can be downloaded by clicking on the thumbnail images.

Some of the transcriptions give dates, showing that Fenwick received at least one tune from James Reid in 1860, and that others were sent to him by Elizabeth Oliver (née Reid) in the 1880s. Fenwick’s careful recording of the dates and his quotations from Elizabeth Oliver’s letters suggests that he regarded her information as important.

In one of the annotations Fenwick quotes a postscript in a letter from Elizabeth Oliver in which she specifically mentions that using keyed notes available on a 14-keyed chanter will improve the tune, which seems to imply that she herself played such a chanter.

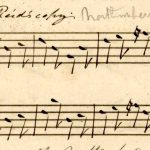

“Highland Laddie with Vars” (Tune 34 in Fenwick) appears on a page of tunes marked ‘Northumbrian small pipes without keys. G drones in unison‘. The tune is annotated ‘James Reid’s copy to J W Fenwick‘. This tune has several versions and variants; this one is the tune often known as ‘Kate Dalrymple’. This Reid version is extremely close to Peacock’s ‘Highland Laddie with Variations’ (Peacock No.50) except that one variation appears out of sequence.

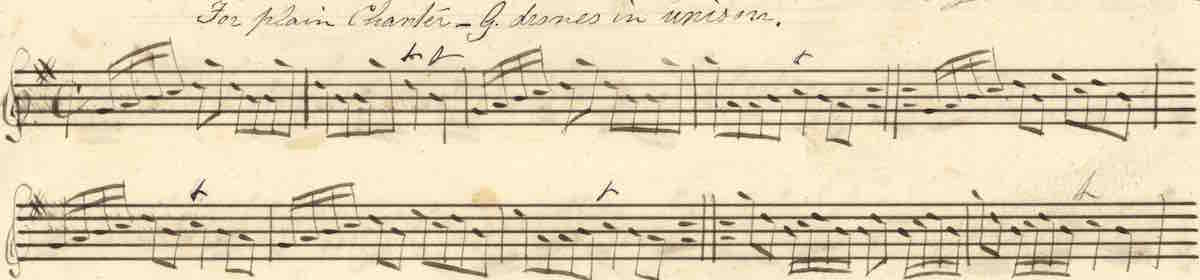

“Jackey Layton with Vars” (Tune 35) is also listed under ‘For plain chanter – G drones in unison’, and carries the annotation ‘James Reid’s copy to J W Fenwick‘. The tune, essentially the same as that given in ‘Northumbrian Minstrelsy’ is followed by five variations. (cf. Tune 90, below)

“Shew’s the Way to Wallington” (Tune 68) appears with the annotation ‘James Reid’s Copy to J W Fenwick 1860‘. It is listed as a tune for the six-keyed chanter, but this has subsequently been crossed out (in pencil). The crossing-out is itself erroneous, as the tune requires a low F♯, the first keyed note below the fingered low G of the keyless chanter. The B part of this version of the tune differs from the better-known version that appears in ‘Northumbrian Minstrelsy’.

“The Major” (Tune 71) has the annotation ‘Jas. Reid’s copy‘. It also appears in similar form in ‘Northumbrian Minstrelsy’. This version appears to be a short and simplified version of a tune that was published in Geoghegan’s ‘Compleat Tutor For the Pastoral or New Bagpipe’ c.1746 in London, and also appeared elsewhere, including the Vickers manuscript tune book of 1770, in Northumberland.

“The Dorrington Lads” (Tune 73) bears an extended annotation testifying to its significance in the Northumberland piping tradition: ‘As played by Robert Reid of North Shields & his son James, also his Daughter Elizabeth Oliver. Mrs. Oliver, in a letter to me dated August 8th/83 says “most likely the same copy that poor Will Allen was trying to play when his Spirit was called Home to a more blissful rest”. P.S. if you have a 14-keyed chanter you will find by using the B♭ & F♮, B flat & F natural, in the first part of the tune a great improvement. it is not marked so in the tune there being neither B♭ nor F♮ when it was written. E. Oliver.‘

This is significant in several ways, in that it identifies as a Robert Reid tune; it confirms a link between the playing of Robert Reid and that of Will and James Allan, and supports the account of Will Allan’s death which appears in ‘The Life of James Allan’. Elizabeth Reid/Oliver’s comment might also suggest that the taste for the modal sound of some earlier music was diminishing, and further suggests that she had a 14-keyed chanter, which is thought to have been the point of development reached by Robert Reid; Elizabeth was 18 when her father died but had one of his most advanced chanters.

“My Ain Kind Dearie” (also numbered as Tune 73 by Fenwick, presumably in error). The tune has the annotation, ‘Mrs. Oliver’s copy, to Mr. Fenwick, June 30th/1883.‘ This version of the tune appears to be identical, including the gracing and trills, to that in the published edition of Peacock’s tunes, with the exception that the publication gave no time signature. The tune is also know as ‘Lea Rigg’; Robert Burns names the tune for his ‘improved’ song, ‘My Ain Kind Dearie’, suggesting that ‘Lea Rigg’ is the earlier name.

“I cannot get my Mare tane” (Tune 74) carries the annotation ‘Mrs. Oliver’s copy. same air is in Peacock’s book.‘ This annotation is most confusing; this air does not appear in Peacock’s published book, although the title is sometimes attached to a version of ‘Highland Laddie’. In the NPS facsimile of Peacock’s Tune Book, Say & Ross state that three known copies of Peacock have the title of one of his versions of ‘Highland Laddie’ annotated with the ‘Mare’ title, and Seattle states that Crawhall also links the ‘Mare’ title to a version of ‘Highland Laddie’. Later in his manuscript Fenwick attributes this title to a version of ‘Highland Laddie’ which does appear in Peacock.

This tune, No.74, though, does not relate to the known versions of Highland Laddie.

“Roses Blaw” (Tune No.75) has the annotation ‘James Reid’s copy‘ followed by a further pencilled note ‘Northumbrian air‘. This is a version of a tune that appears in ‘Northumbrian Minstrelsy’ as a song, and is more commonly known by the longer name ‘O, I hae seen the roses blow’.

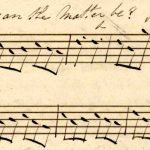

“Oh Dear! What can the Matter be” (Tune 76) has the annotation ‘Jas. Reid’s copy. for the plain chanter {about 1790}‘ and carries the playing instruction ‘Gracefully‘. This version gives the tune only, although it is now more usually played with variations.

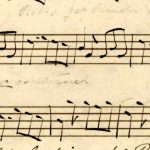

“The Holey Halfpenny” (Tune 77) has the pencilled annotation ‘Robt and Jas Reid’s copy JWF‘. Only the two parts of the tune itself is given, although the tune is now more usually played with variations, as a concert or ‘display’ piece.

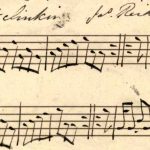

“Fill the stoup an’ haud it clinkin'” (Tune 78) has the simple annotation ‘Jas. Reid’s copy JWF‘. This is an old Scottish tune that appeared in several 18thC and early 19thC publications.

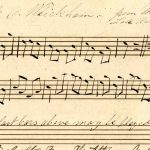

“The Black Cock of Whickham” (Tune 80) has the annotation ‘from Mrs E. Oliver (daughter of the late Robert Reid of North Shields) sent Sept 25/84‘. The transcription includes an alternative arrangement of triplets for the last two bars. The name refers to the traditional ‘sport’ of cock-fighting.

“Jack Latin with Vars.” (Tune 90) has the annotation ‘from an old printed copy formerly in the possession of Jas Reid, No. Shields‘. This variation set is not the same as that given as Tune 35 (above), nor is it the same as the tune in Peacock. The old printed copy has not yet been identified.

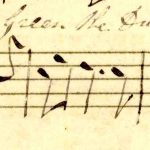

“Maggie Lauder with Var,s” (Un-numbered in Fenwick). This tune is not a transcription by Fenwick. It is written on a piece of blue paper than has been carefully pasted into the book. The title and notation is not in Fenwick’s hand, but the following annotation is probably Fenwick’s: ‘Mrs. Oliver’s Copy, as she learned it from her father, the late Robert Reid of North Shields‘.

Examination of the paper shows that the tune is written on the reverse side of a printed pro-forma, the staves being hand-drawn. One side edge of the paper (the left edge of the printed pro-forma) is the original edge, as is to top edge of the paper, the other edges have been very neatly torn, probably using a ruler and/or a paper knife. Although the paper is pasted into the book, it is possible to see that the printed side of the pages is ruled feint with about 40 horizontal lines for writing, and divided vertically into columns by red single or double lines. It is probably a recording or accounting form of some sort.

Between the first and second staves there is a line of indentations left by typewriting on the pro-forma side. Although reversed, they reveal that the columns were headed No. / Name / Occupation // followed by repeated sets of columns allowing a daily entry M / T / W / T / F / S / S //. There are two full weeks shown and the M from a third.

The pro-forma is otherwise unused. Consideration of this form suggests that it came from a commercial organisation with a large workforce comprising a variety of occupations. The organisation was large enough to warrant using forms rather than a hand-written ledger, investing in a typewriter (the machine) and employing a Typewriter (the person who operated the machine) to maintain daily records.

John Oliver, Elizabeth’s husband, was a Colliery Viewer (Manager) in South Wales, and it is at least possible that this paper is part of a ‘recycled’ colliery recording / accountancy form.

G G Armstrong copied this tune (his copy is now in the Morpeth Chantry Bagpipe Museum) and his transcription was used for the tune as printed in NPS Tunebook 3 (1991).

TUNES POSSIBLY IN THE REID REPERTOIRE

Chevy Chase is a ceremonial tune associated with the dukes of Northumberland. James Reid must have been expected to play it after his appointment in c.1858 as Assistant Piper to Thomas Green, the ducal piper. Fenwick includes the tune with the annotation ‘Chevy Chase, as played by Mr. Thos Green the Duke of Northumberland’s Piper‘ (Tune 91).

It’s seems at least feasible, and even probable, that James Reid would have played Thomas Green’s version of the tune, at least after 1858.

On 24th January 1823 Robert Reid played pipes for the twentieth annual supper of the Burns Club at Miss Lowsey’s Bridge Inn at Bishopwearmouth, in Sunderland:

Both Robert (II) and his father Robert (III) were alive at this time, and without corroborating evidence it is not possible to be certain about which was playing. The spelling REID, however, seems to be more associated with Robert (III), and despite the unreliability of spelling in reportage of names, we might make a tentative assumption that this refers to Robert (II).

The detailed article states that throughout the evening Reid played ‘appropriate airs’ after each recitation or song, and lists the recitations and songs; they include several Burns works which have tunes associated with them, and it is easy to speculate that Robert might have adapted his repertoire to the occasion and played those Burns-related tunes, including perhaps;

- Scot’s wae hae wi’ Wallace bled

- Corn Riggs

- My Nannie O

- Ye Banks and Braes o’ Bonny Doon

- The Birks of Aberfeldy

Given that ‘My Ain Kind Dearie’ is a Robert Burns song to the tune ‘Lea Rigg’ it is possible that he played that, too.

There is another report showing that Robert Reid played again at the same annual dinner in the following year, 1824.

This page will be updated, expanded and amended as research allows.